Is there a Department of Scare Creation at Case Western? This week, we have research reported by their Dr. Scott Frank and colleagues: “Hyper-texting and Hyper-networking Pose New Health Risks for Teens.” Frank says,

The startling results of this study suggest that when left unchecked texting and other widely popular methods of staying connected can have dangerous health effects on teenagers.

(Aside to Dr. Frank: C’mon, doc. Do you not know that “hyper text” is already a term in wide usage? Do you know how sometimes there are underlined words, most often in blue, that, if you click on them with your mouse then you are magically transported to another website? That’s it. Do you realize that any teens who aren’t already laughing at you for your transparently hysterical research agenda have cause to snicker over your misuse of contemporary language? But back to my point…)

The subject of a press release by the American Public Health Association, the study claims that teens who text more than 120 times a day are, compared to light texters:

- 41% more likely to have used illicit drugs

- Nearly 3.5 times more likely to have had sex

- 90% more likely to report having had four or more sexual partners

The results were based on a survey of over 4,000 high school students in the midwest.

The paper, presented at the annual meeting of the APHA, is yet another indicator of the association’s redirection — from promoting social reform to becoming the Popular Front for the Promotion of Family Values. The news media complied with the APHA’s mongering by publicizing Frank et al.’s findings, for instance here, and so did the usually serious WebMD.

Research like this is meant to say both “childhood is deadly” and “children are dangerous.” Teenagers have sex, it says, and you grownups shouldn’t take that lightly.

The connection of teen sex and teen drug use to cell phones, iPhones, or the Internet appeals to people who think there is something new, and terrifying, about modernity. As Carl Phillips notes over at ep-ology, it’s a way of saying “Beware the scary new technology! It is causing teens to interact.”

Of course, there’s also a race, class, and sex angle: The study reported that excessive texting (along with what the authors call “hyper-networking,” meaning excessive use of social network sites) is more common among girls, racial minorities, and kids whose parents have less education. One more reason to be suspicious of the poor and the dark-of-skin, says the Popular Front.

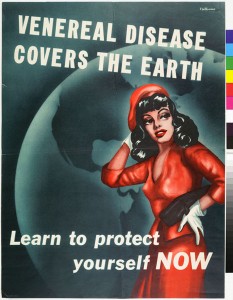

Especially, the APHA wants us to beware of girls. The public health industry — the folks who reminded your grandparents that female sexual desire spreads disease with posters like this one, from the ’40s:

… now tell us to watch out for girls who text.

Mike Stobbe at AP, covering the report, did a (typically) good job of looking deeper into the question. About half of kids between the ages of 8 and 18 text each day, and the ones who do average 118 texts per day. While texting while driving is a really bad idea, texting about sex isn’t uncommon (Stobbe points out). Unlike texting while driving, nobody dies from it.

Public heath shouldn’t be a matter of, as the Frank report put it, wake-up calls for parents. Childhood really is dangerous in some places (Somalia, Congo, and Haiti come to mind, in case physician-researchers currently obsessed with sex amongst American teenagers are looking for something useful to do with their medical skills). But it isn’t in America. Sex, even between teenagers, really isn’t very scary. There are a lot of things we adults could do to make the country and the world less miserable, but spying on our kids isn’t among them.